fossilshk

(Lung)

管理員

UID 1

精華

23

積分 4775

帖子 2827

閱讀權限 200

註冊 2006-7-14

來自 中國/香港

狀態 離線

|

[廣告]:

Darwinopterus, the remarkable transitional pterosaur

Pterosaurs - the charismatic flying archosaurs of the Mesozoic Era - fall fairly nearly into two great assemblages: the primitive, mostly long-tailed basal forms (or 'rhamphorhynchoids') and the more strongly modified, consistently short-tailed pterodactyloids. Pterodactyloids emerged in the Middle Jurassic and persisted to the very end of the Late Cretaceous, and fossils show that they did an awful lot more in their evolution than did non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs. Several lineages evolved giant size, and bizarrely specialised skulls and dentitions show that they took to filter-feeding, mollusc cracking, and perhaps to frugivory, carrion feeding and terrestrial stalking (Wellnhofer 1991, Wellnhofer & Kellner 1991, Unwin 2003, Witton & Naish 2008). A list of anatomical characters show that pterodactyloids are most closely related to the rhamphorhynchids (Kellner 2003, Unwin 2003) - a group of Jurassic non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs that have a relatively low number of needle-like teeth and are best known for Rhamphorhynchus from the German Solnhofen Limestone. While intermediates between rhamphorhynchids and pterodactyloids are hypothesised to have existed, they have remained unknown. Until now [image above shows Darwinopterus predating on small maniraptoran theropod: image by Mark Witton].

Today see the publication of a remarkable new kind of pterosaur that bridges the gap between non-pterodactyloids and pterodactyloids, and it exhibits a surprising melange of characters. Named Darwinopterus modularis Lü et al., 2009, it's from the Tiaojishan Formation of Liaoning Province, China. The age of the Tiaojishan Formation has been controversial, and until recently many workers regarded it as Lower Cretaceous. However, the most recent work indicates a Middle Jurassic age (see supplementary data in Lü et al. (2009)). This is significant for reasons not related to pterosaurs, as the Tiaojishan has yielded small feathered maniraptoran theropods, most notably the troodontid Anchiornis (Hu et al. 2009: originally identified as a basal bird, and discussed as such here on Tet Zoo. Shown here, as restored by Hu et al. (2009). Wow, those feathered dinosaurs sure did look stupid). Anyway, the new taxon's name of course commemorates the 200th anniversary of Darwin's birth and 150th anniversary of the publication of Origin: a very fitting name, given the fact that - as we'll see - Darwinopterus represents a transitional fossil of the sort that Darwin predicted.

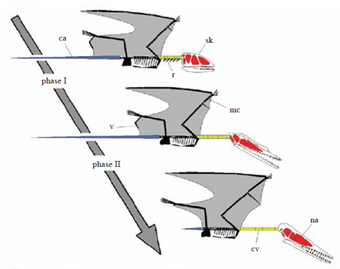

Like rhamphorhynchids and unlike pterodactyloids, Darwinopterus has a long fifth toe composed of two elongate phalanges, a proportionally short metacarpus, and a long tail with 27 vertebrae. These features are absent throughout pterodactyloids and are characteristic 'basal pterosaur' features. When alive, Darwinopterus would have superficially resembled a rhamphorhynchid, with a broad and obvious cruropatagium (the membrane that stretched between the fifth toes of both feet and incorporated the tail base), relatively short wings, and probably a diamond-shaped structure at the tip of its long tail.

Yet the great paradox about Darwinopterus is that it combines this archaic body plan with a neck and skull that look like that of a fully-fledged pterodactyloid. In short, Darwinopterus looks like a weird hybrid: a pterodactyloid head on a 'rhamphorhynchoid' body.

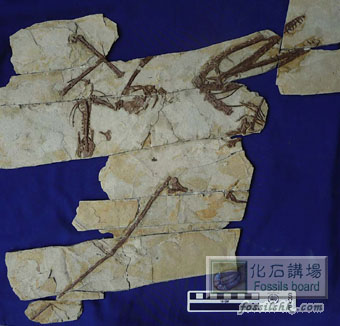

It seems reasonable to wonder whether this association is genuine. Happily, we can reject any possibility of fakery or chance association: the type specimen is - while not preserved in complete articulation [it's shown above; image courtesy of D. M. Unwin] - convincingly associated (that is: it's obvious that the skull and neck really do belong together with the rest of the skeleton). Even better, more than one specimen is known (like, about 20!), and at least one of these does have the head-neck ensemble articulated with the rest of the skeleton.

Interestingly, Darwinopterus's skull [shown above; image courtesy of D. M. Unwin] doesn't just recall that of a generic pterodactyloid, but specifically resembles such pterodactyloid taxa as the dsungaripteroid Germanodactylus. This at least suggests the possibility that the skull morphology seen in some basal pterodactyloids is a plesiomorphic hangover, and we may have to change some of our views on character polarity. A low, bony crest with a fibrous surface texture extends along much of the length of Darwinopterus's forehead and snout, and the nostril and antorbital openings are combined to form the nasoantorbital opening typical of pterodactyloids. The neck is proportionally long (even for a pterodactyloid).

Darwinopterus the modular pterosaur

So it's almost as if the head and neck were evolving at different rates from the rest of the body: in other words, Darwinopterus looks like a classic case of 'mosaic evolution' or modularity (hence the species name). This much-discussed evolutionary phenomenon has been considered controversial, in part due to a lack of good examples: Darwinopterus looks like one of the best yet discovered, and this isn't lost on Lü et al. (2009).

Phylogenetic analysis confirms that, as strongly suggested by its apparent transitional nature, Darwinopterus is the sister-taxon to Pterodactyloidea (it has to be outside of this major clade, as published definitions are node-based*). Lü et al. (2009) found the Darwinopterus + pterodactyloid clade to be well supported in their analysis, and named it Monofenestrata. This is a reference to the evolution of the combined nasoantorbital fenestra, an autapomorphy of the clade, and previously thought unique to Pterodactyloidea [adjacent 'family tree', from Unwin (2003), shows simplified relationships between the pterosaur groups. Basal pterosaurs, aka 'rhamphorhynchoids', are down at the bottom in blue; pterodactyloids are in purple].

* Kellner (2003, p. 117) defined Pterodactyloidea as 'the most recent common ancestor of Pterodactylus and Quetzalcoatlus and all their descendants', and Unwin (2003, p. 158) defined it as 'Pteranodon longiceps, Quetzalcoatlus northropi, their most recent common ancestor, and all its descendants'. Both definitions are unsatisfactory. Kellner's would exclude ornithocheiroids if Unwin's topology is correct. Unwin's rests heavily on the hypothesis that ornithocheiroids (including pteranodontids) are the most basal clade within Pterodactyloidea: if ctenochasmatoids, or dsungaripteroids, are more basal than pteranodontids (as they are in many phylogenies) then they're excluded from Pterodactyloidea under his definition!

Aerial predation at the root of a radiation?

What, then, was Darwinopterus doing? We don't know, but we can make some good guesses. The rhamphorhynchid-like post-cervical skeleton of Darwinopterus was not well suited for terrestrial locomotion: its hindlimbs were short and weak, hindlimb movement would have been somewhat restricted by the large cruropatagium, the wrist region was short, and the wings were poorly suited for quadrupedal support. This description applies to non-pterodactyloids in general, and it seems that basal pterosaurs were all poor terrestrial locomotors, at least compared to pterodactyloids. And, in contrast to some other non-pterodactyloid pterosaurs, there are no indications that Darwinopterus was a proficient climber. Nor does it have any features that might be associated with swimming or diving. So, we can hypothesise that Darwinopterus was an aerial predator, doing whatever it did while on the wing.

Darwinopterus combines a proportionally huge, long-snouted skull with slender, widely spaced, spike-like teeth and a proportionally long, relatively flexible neck. One interesting possibility suggested by this combination of features is that it was an aerial predator of other flying vertebrates. Indeed, we know that Darwinopterus was contemporary with smaller pterosaurs, small gliding maniraptorans and gliding mammals. In fact, is it coincidental that this possible aerial predator appears in the fossil record at the same time as the earliest aerial maniraptorans? As regular readers of Tet Zoo will know, bats have become dedicated predators of other flying vertebrates (birds in particular) on several occasions, and it's always been surprising that pterosaurs didn't. Perhaps they did, though we need more analysis and better data before we can be at all confident about this [adjacent image shows the predatory phyllostomid bat Chrotopterus auritus eating a smaller bat. It was previously featured in this article on the evolution of vampires, and originally came from a website called Tropical Bats, now unfortunately defunct and unfindable].

Given that Darwinopterus was at the base of the largest and most diverse pterosaur clade, its anatomical and behavioural specialisations may well have set the stage for what was to come. How neat if aerial predation of little theropods 'drove' the early stages of the pterodactyloid radiation.

#scienceblogs.com

|

|

|